To assist in social distancing, the Paul Lukez Architecture (PLA) office shifted to a remote access system to enable everyone to work from home. Since then, we have found our new routine to be our friend.

We begin each week with our Monday morning online meeting, and we have become even more familiar with connective technologies. You can find us chatting with clients and contractors on pretty much any platform. We Zoom, we Skype, we join.me, we Teams, and we Trello. We even use the phone! We are constantly in touch with one another, and we check in with Paul on a regular basis. Everybody can authenticate to the office server from home, and during our meetings, we have come to know one another’s unique and comfortable home offices. Our personal spaces are combining to both create and re-create our amazing team dynamic, just as if we were sitting next to one another in the office.

Furthermore, we are using our favorite technologies more than ever, while discovering new software that advances communication with each other and with our clients. Being open-minded, flexible, and empathetic is how we work successfully as a team, and this spirit is our special key to bringing us closer than ever before through the avenues of these technologies, despite the social distancing.

Working remotely also reminds us that our work is not our job. A job is what we do every day, but our true work is to look after one another, to grow together as a team, and to create a sustainable, healthy business model that benefits everybody.

In early March, we implemented enhanced measures beyond scheduled cleaning. Twice a day we sanitized doorknobs, thermostats, the coffee machine, switches, working surfaces, and the bathroom. At the front desk, we provided PLA-formulated alcohol-based hand-sanitizer with added aloe. We made it convenient to open doors with paper towels, and we reminded ourselves to wash our hands periodically throughout the day.

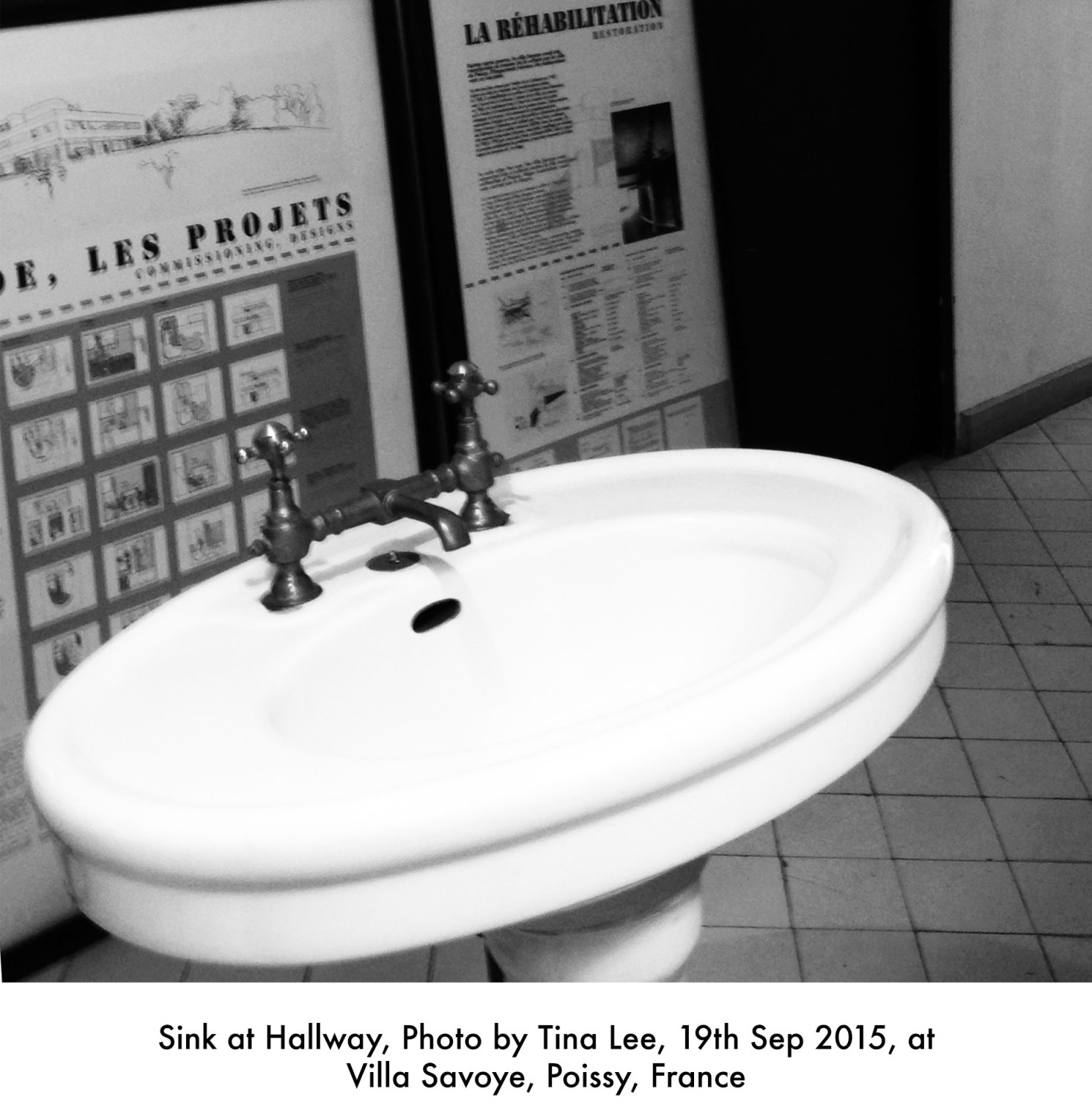

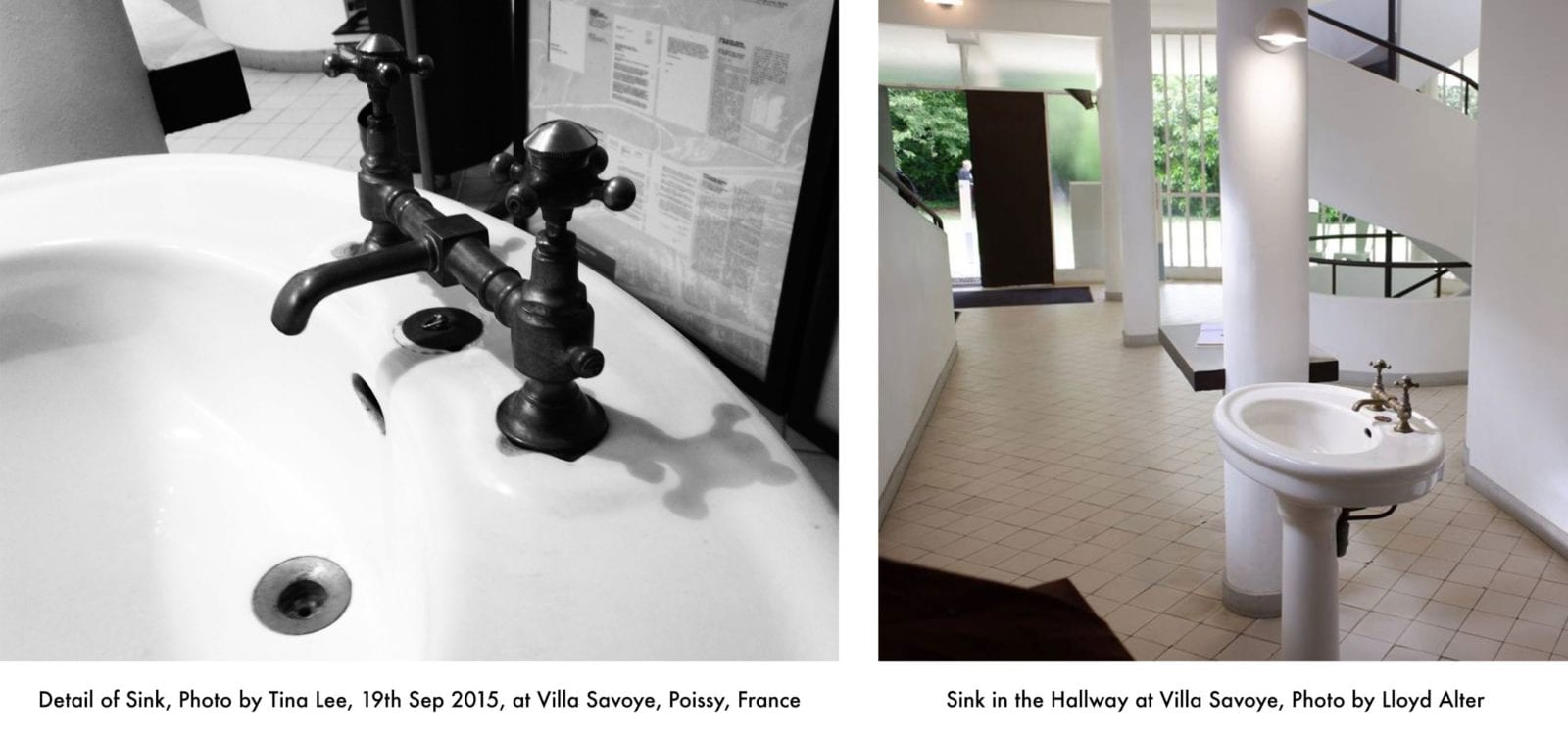

On a Thursday evening, Paul was sharing with us his thoughts on “Design and Health” and how to make health measures more amenable to cities. Our conversation reminded me of the University of California–Berkeley Professor Greg Castillo’s course, “Architectural History: Design Discourses and Practices,” and my trip to Villa Savoye in Poissy, France.

A small but profound memory I have from my trip to Villa Savoye, designed by Le Corbusier in the 1930s, is the sink placed at the entry of the hall. Professor Castillo told us that the client of Villa Savoye was a doctor in the time of tuberculosis and was obsessed with the bacterial transmission that often caused this condition to spread.

To improve hygiene and sanitation, Le Corbusier located the sink surprisingly close to the entrance of the building, just after the ramp but well before the spiral staircase, to remind guests to wash their hands before entering the house.

That unconventional floor plan reminds us that design has the power to shape how we live and to suggest a healthier lifestyle and routine for us. A sink at the doorway can remind us to wash our hands when we arrive or when we leave, similar to the cleaning ritual at Japanese shrines. Perhaps a small changing room at the doorway can remind us to remove our outdoor clothes and shoes before we reach a more private space at home. Perhaps a special vestibule/foyer design can separate the outer and inner spaces and help prevent us from tracking bacteria, parasites and pollutants into the house, as the Japanese do with the genkan, an entryway right inside the front door for removing shoes before entering the main part of the building.

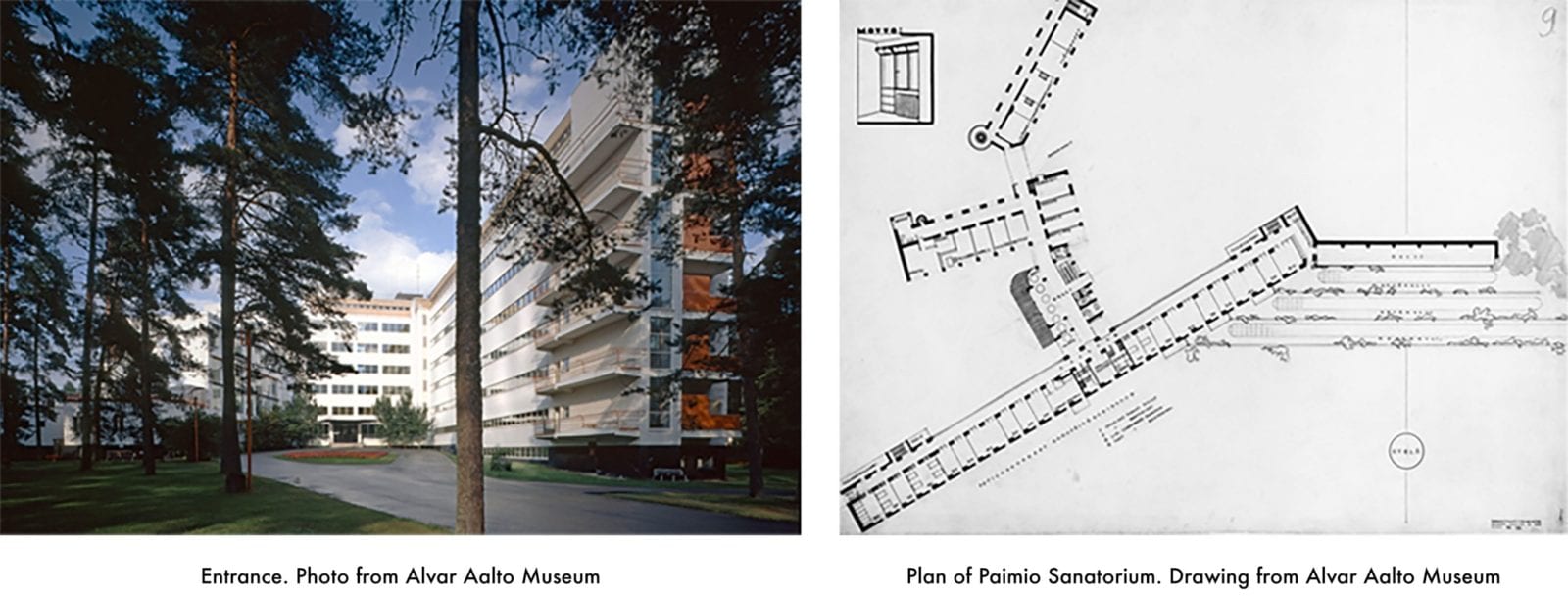

Villa Savoye is but one reminder of Design and Health. Another case study shared by Professor Castillo is the Paimio Sanatorium, near Turku in southwestern Finland, by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto.

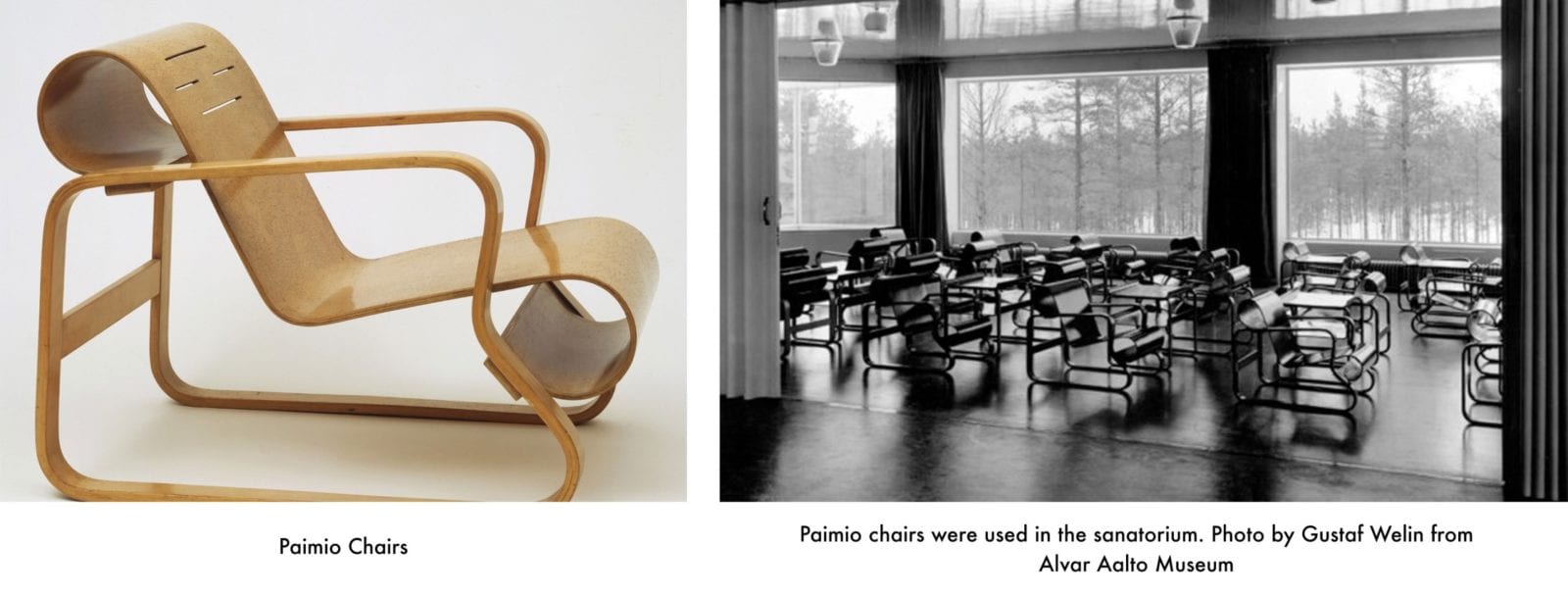

The sanatorium was inaugurated in 1933 at a time when tuberculosis was a much-feared disease. Aalto designed not only the building itself but also the interior space, furniture and fixtures, giving them all the common purpose of helping the patient recover and heal.

Quoted from the Paimio Sanatorium: “Site Plan & Floor Plan—it was asymmetrical and non-rectilinear, but at the same time was based on a controlled system of coordinates. The seven-story building had balconies at the end of each residential wing, so weaker patients didn’t have to go far to reach them. Patients who were more mobile took the sun and fresh air on the roof terrace.”

“Paimio Chair—was made from bent birch plywood, which made it easy to clean, and was angled to ease the patient’s breathing.”

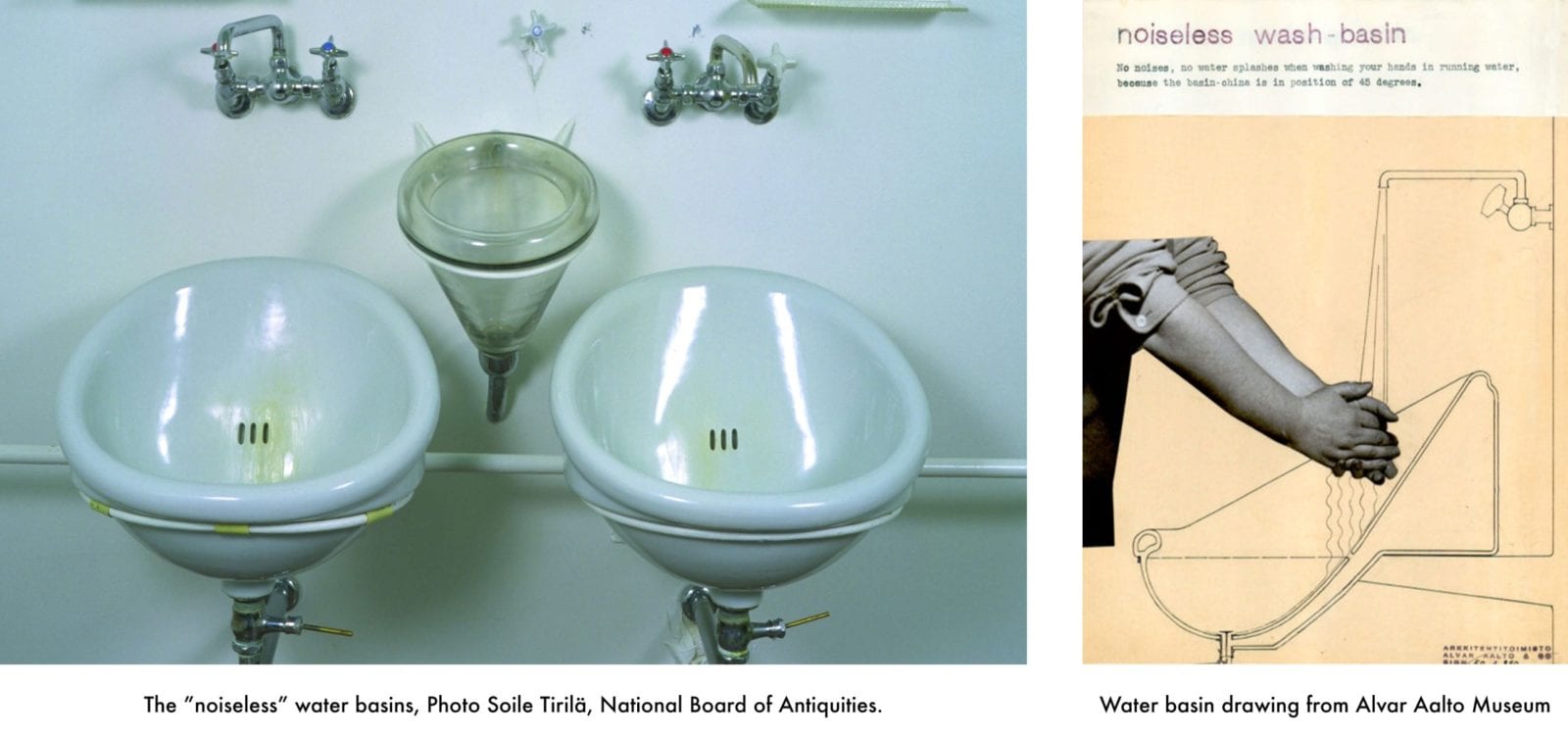

“Water Basin—custom sinks in Paimio minimized noise, so as not to disturb the patient’s roommate, and splash, to keep germs from spreading.”

These very human-centric design choices remind us that modern architectural design can pay greater attention to our senses, physical form, and the total comfort of the human body. It also demonstrates to us that, when a designer places interior space, furniture and fixtures on an equal footing with form and structure, a very holistic design can result.