Hamburg, Germany – where negative impacts of climate change become positive opportunities for urban transformation.

This post is part one in a series from Paul Lukez Architecture highlighting resilient cities’ future-proofing strategies.

The constant drumbeat of negative news about climate change is unrelenting and distressing. The recently released reports by the EPA and other organizations about the impact of climate change on our planet and its habitable places, especially those located in low-lying coastal districts, can appear overwhelming.

What can we do?

At first glance, the three Fs (Fighting, Fleeing or Floating) appear to be our only options. Fighting climate change involves creating defensive barriers (e.g., dikes and sea walls) or developing new carbon absorption technologies. Fleeing our urban communities and moving to higher ground is also a theoretical possibility, if not a necessity. Alternatively, we can also consider staying put by floating in place, as opposed to remaining on terra firma that is subject to flooding.

Positive options and opportunities for transformation

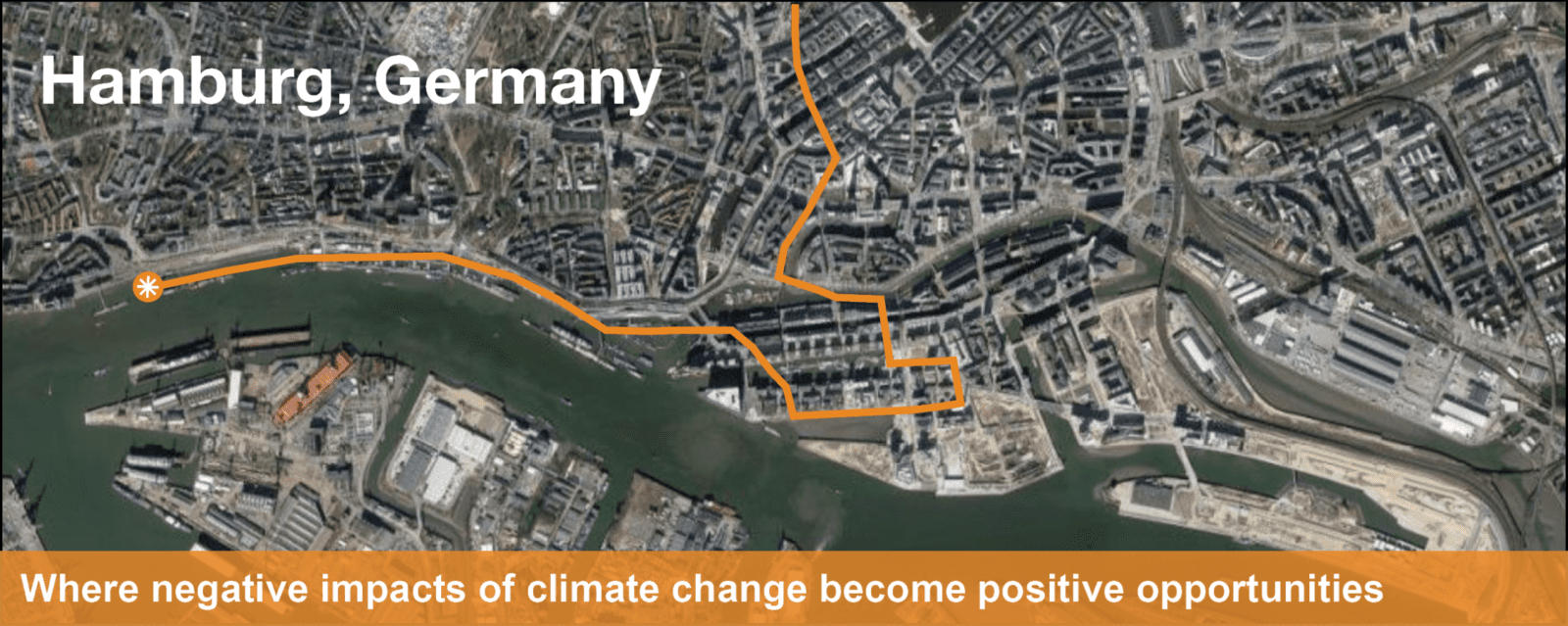

Hamburg, Germany, offers another possibility, though. Located on the Elbe River, this major harbor city regularly witnesses the impact of climate change, especially when North Sea storm surges are funneled some 60 miles downriver toward the city. Hamburg’s planners have shown us another way to survive the effects of rising seas. They have employed creative design and engineering solutions to protect the city and enrich it with a new dimension of urban experience that creates better forms of urbanity and enhances urban services, experiences, and amenities for residents and visitors.

A lucky visitor

I was lucky to visit Hamburg on a beautiful fall weekend. Its harbor area was flooded with families and visitors of all types who were enjoying the unexpected good weather and the harbor district’s rich range of experiences. My goal was to explore HafenCity, a formerly gritty harbor district transformed into a model for resilient urban design, so I extended my walk along the river promenade (Grosser Elbstrasse) to the Fish Market area. This post describes some of the design and engineering strategies I observed that illustrate how utility and beauty can be combined to protect Hamburg’s residents from the effects of climate change.

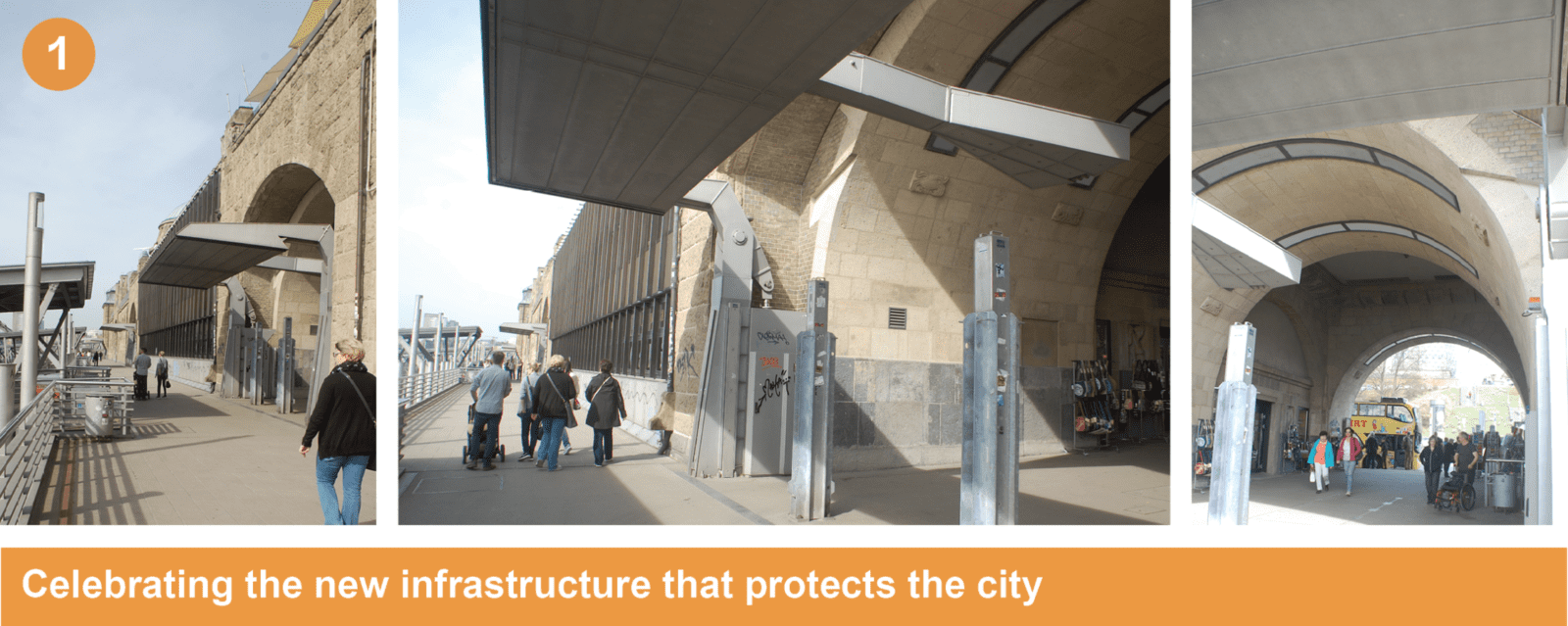

HafenCity and neighboring districts integrate a rich infrastructural network of elevated promenades and public places. Major barriers operate like dikes but are often sculpted into broad walkways, boulevards or parkways. Their elevated profiles seamlessly blend into the cityscape and waterscape. As the flood barriers touch the water, they become public spaces of all types—amphitheaters, stepped landings, terraced parkways, etc.—all part of a network of bridges, ramps, and sluices. At every turn, pedestrians are surprised by the types of urban amenities and infrastructures they encounter as they traverse this network. Hamburg’s designers and planners have demonstrated that protective infrastructure can be attractive while providing recreational amenities.

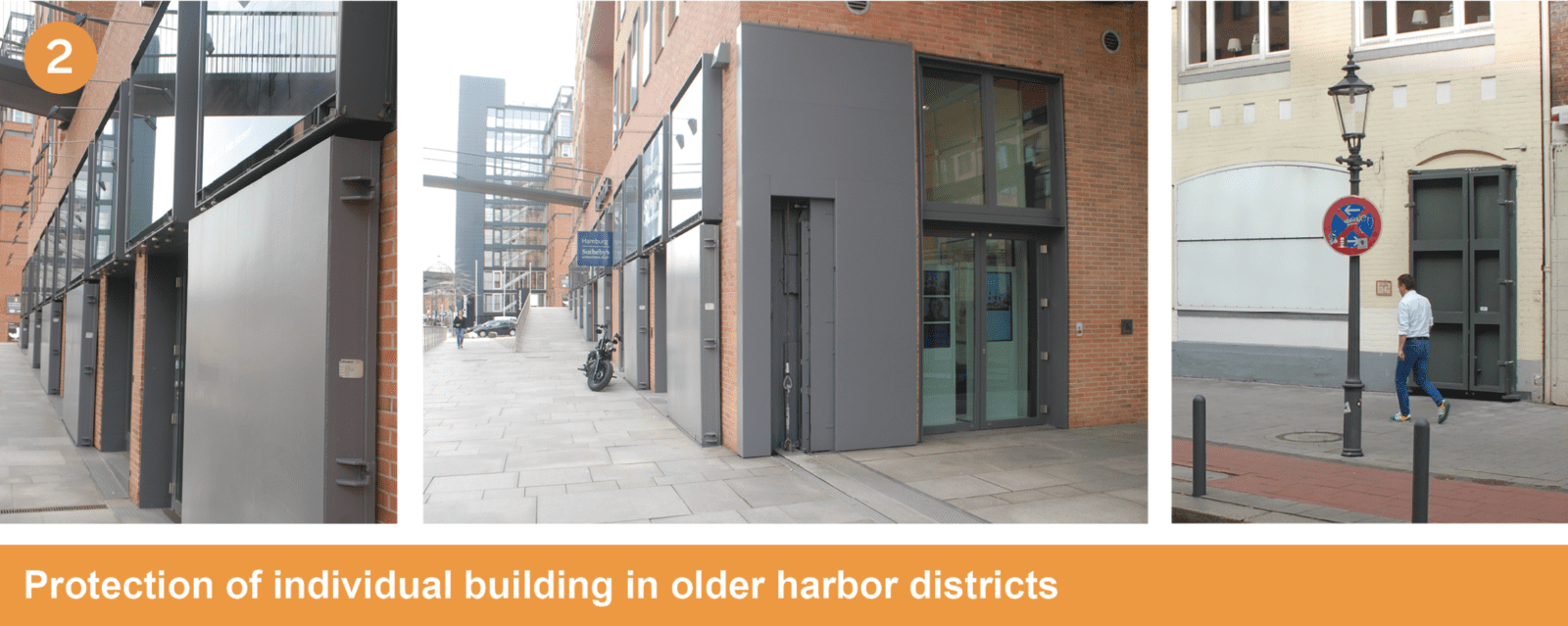

Some of these buildings are built at lower elevations, thus more exposed to rising seas and flooding. So each building’s lower level must be secured from these hazards by integrating a system of sliding steel doors and gates into its ground floor, such that, when a storm hits, the steel gates close to protect the building’s interior spaces. This strategy distributes the financial responsibility of protecting at-risk real estate to private property holders, while the public sector coordinates incentives for adapting this protection strategy.

In the newer HafenCity area, all new buildings are raised on higher foundations when possible, so their most vulnerable areas are protected from rising sea levels. All private living spaces are above flood levels.

This strategy recognizes the impossibility of protecting all parts of the city from floodwaters. By embracing floodwaters in some areas, such as public parks and plazas, other areas are relieved of additional stresses on their flood protection infrastructure systems. Consequently, many of HafenCity’s public parks and plazas are designated as flood zones that readily absorb and embrace floodwaters.

People are naturally attracted to water. They gravitate toward it whenever possible. Hamburg’s waterfront has been made publicly available and integrated into a necklace of public walkways and spaces, allowing people to promenade along the harbor’s edge. Now, from parks, terraces, bridges, and boats people can observe the active harbor and its vessels crisscrossing the Elbe River. Stairs and terrace plateaus cascade toward the water’s edge, offering an additional wide range of urban experiences.

Conclusion

As discouraging as the news of the effects of climate change on our planet’s habitats may be, this environmental crisis invites planners, designers, engineers, scientists and citizens to collaboratively invent new solutions that address the underlying problems of climate change and adapt our natural and built environments to it in socioeconomically fulfilling ways. Hamburg’s HafenCity offers us a proven model for achieving this goal.